The phrases have tripped off the tongues of the Taliban for quite some time.

“We’re working to establish an inclusive government that represents all the people of Afghanistan,” promised Taliban leader Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar when he recently arrived in Kabul to start talks aimed at forming a leadership to move the movement from guns to the government.

“We would like to live peacefully,” vowed Taliban spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid at the first press conference in the capital after the Taliban suddenly swept into power on 15 August. “We don’t want any internal enemies and any external enemies.”

Judge them by their actions, not their words, has become the mantra of a fast-expanding league of Taliban watchers including Afghans, foreign governments, humanitarian chiefs and political pundits the world over.

But Afghans are watching most closely of all. They have to.

On a day when brave protesters with bold banners spilled into the streets of Kabul and other cities – Afghan women leading the charge to demand their rights, their representation, their roles in society – the new Taliban government was unveiled.

Was this more evidence of the media-savvy Taliban? It temporarily knocked news of Taliban firing guns in the air, wielding rifle butts and sticks to disperse protesters, out of the world’s headlines.

But it was a modest ceremony, in the mundane setting of a press conference, for such a momentous, much-anticipated message. It electrified social media and delivered a gut punch to those who had held fast to Taliban promises.

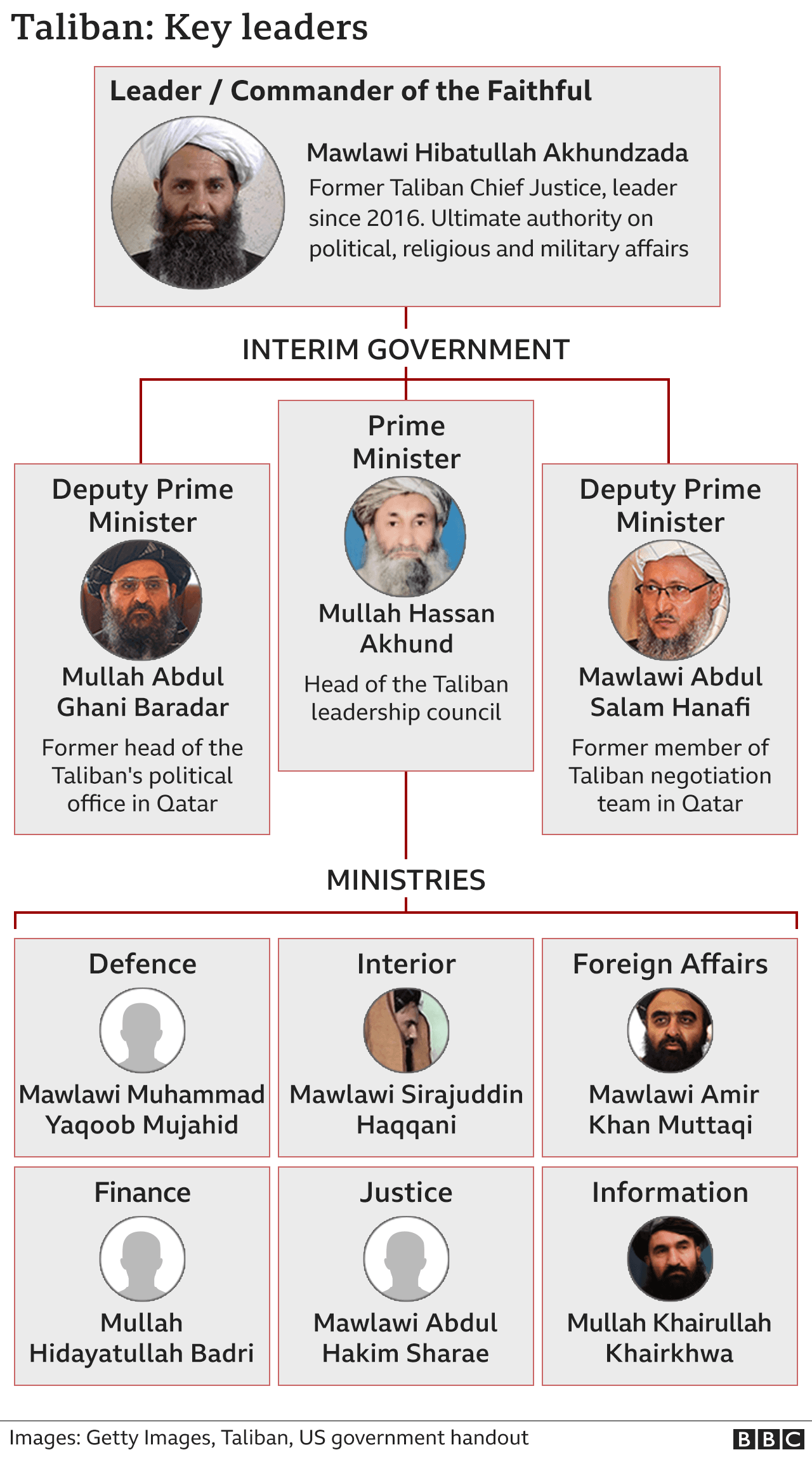

Far from being inclusive, it is exclusively Taliban. The old organigram of the Taliban movement, with its commissions, deputies, and the all-powerful Emir Hibatullah Akhundzada, has been transplanted into a cabinet with the same political architecture of governments everywhere.

The reviled Ministry of Vice and Virtue is back; the Women’s Affairs Ministry is out. Its makeup is overwhelmingly drawn from Pashtun tribes, with only one Tajik and one Hazara, both Talibs. There’s not a single woman, not even in deputy minister positions.

It’s a government of the old guard, and the new generation of mullahs and military commanders: men in charge when the Taliban ruled in the 1990s who return, beards much lighter and longer; former Guantanamo Bay prisoners; current members of US and UN black lists; battle-hardened fighters who pressed forward on every front in recent months; self-styled peacemakers who sat around negotiating tables and shuttled around regional capitals with promises of a new Taliban 2.0.

image source Reuters

image source ReutersSome names stick out – some so far they can seem provocative.

The caretaker head of cabinet is the white-bearded Mullah Hasan Akhund, a founding member of the Taliban who’s on the UN’s sanctions list.

The caretaker Minister of the Interior is Sirajuddin Haqqani. His face has rarely been seen except in a photograph, partially obscured by a caramel-colored shawl, in an FBI wanted poster announcing a big bounty of $5m that’s also on his head. His more recent claim to fame was an op-ed in the New York Times in 2020 calling for peace which failed to mention that the Haqqani Network named after his family is held responsible for some of the worst attacks on Afghan civilians. The Haqqanis insist there’s no such network; they say they’re part of the Taliban now.

The caretaker Minister of Defence, Mullah Yaqoob, represented by a black silhouette, is the eldest son of the founding Emir of the Taliban, Mullah Omar.

But, wait, this is just a caretaker cabinet.

At the press conference in Kabul, as a raucous chorus of questions rose from journalists in the room, it was said more posts might be announced in time. “We haven’t announced all the ministries and deputies yet so it’s possible this list could be extended,” Ahmadullah Wasiq, deputy head of the cultural commission, told my colleague Secunder Kermani.

This may be the opening political salvo to reward and reassure their rank and file fighters, many of whom have been streaming into Kabul, to welcome the return of a “pure Islamic system”.

It also appears as a carefully constructed compromise. Mullah Akhund suddenly emerged at the top, fixing in place rival political and military heavyweights including Mullah Baradar whom many predicted would take a leading role, instead of a deputy position.

Taliban leaders are said to have pushed back against calls to include political leaders from the past, especially those tainted by corruption, arguing they’ve already had their time at the top.

A phrase still rings in my ears from Taliban negotiator Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai, who’s now been appointed as deputy foreign minister, the same role he held the last time around.

When I asked him in February 2020, after the signing of the landmark US-Taliban deal, what he would say to Afghans who feared their return, he replied with great gusto: “I tell them we will have a government acceptable to the majority.” The word majority was punctuated by a loud emphasis.

In other words, a government dominated by traditional values, not what they mock as Western ideas.

Those were heady days when Afghans dared to hope the worst of the war was over. Later that year, on the first day of formal Afghan talks in the Gulf state of Qatar, a buzz shot through the room when the Taliban hinted they would no longer be demanding an Islamic Emirate; they said they understood its sensitivity.

In talks with female negotiators, they reassured them women could play every role except the president, including government ministers.

That was then. This is now. The Taliban are in charge.

“Those who do not pay attention to the social fabric of Afghanistan will face serious challenges,” warns negotiator and former MP Fawzia Koofi, who heard many of those promises.

That challenge is already crystallizing in protests on the streets, in statements from capitals around the world.

“The world is watching closely,” warned a statement from the US State Department. “Little chance of international recognition of Taliban soon,” declared an editorial in Russia’s Nezavisimaya Gazeta.

And a challenge may even rise from within a younger generation of Taliban.

“We must pay attention to the lessons of history,” a young Talib recently reflected me. He emphasized that if the Taliban tried to dominate again, they could be toppled again, as they were in 2001, as the last government just was. Another expressed unease that mullahs schooled only in religious matters were being given so many posts.

image source EPA

image source EPAIn a statement issued soon after the caretaker cabinet was announced, the Emir noted that “all talented and professional people” were desperately needed for their “talents, guidance, and work.”

But in all his exhortations, it was also clear the bottom line was about strengthening “the system,” the re-established Islamic Emirate. This takes precedence above all else.

In recent days in Kabul, I’ve asked Taliban watchers of various ilk if they thought the leadership would harden over time, or open up.

Powerful winds could tilt them in many directions.

The world’s major aid agencies, who provided around 80% of the old government’s budget, are watching closely.

“They’re in very, very dire straits,” the UN’s humanitarian chief Martin Griffiths told me as he ended a visit where he emphasized the centrality of humanitarian principles and values, including the inclusion of women and girls. Senior officials, he remarked, asked him for patience and advice.

Afghanistan’s new leaders are also under the microscope of jihadi movements worldwide who’ve enthusiastically welcomed a new land of Islamic governance compliant with Islamic Sharia law.

Afghanistan is, to use the expression, “too big to fail”. Warnings about a safe haven for extremist groups, worries about human rights and a deepening humanitarian crisis of hunger and hardship, will concentrate many minds on trying to find a way to work with leaders still finding their way, still rooted in their past, rather than, as yet, a different kind of future.

But that mantra will stick – actions, not words, matter most